What, Like It's Hard?

On Being Based and Adornopilled

In a 2000 episode from season eleven, The Simpsons predicted Donald Trump’s successful presidential campaign. Of course, that was the year Donald Trump ran for president – the second time around. Over the years it has repeatedly been memed that episodes of The Simpsons can uncannily predict the future. Whether centred around plausible predictions, wild guesses, or AI-generated hoaxes, the meme itself is an honest reflection of our contemporary condition.

Like the proverbial monkeys, inevitably producing the works of Shakespeare after infinitely pounding away at typewriters, we implicitly understand that through the sheer quantity of images and narratives which inundate us, the future has already been written. Whatever hasn’t happened yet has, at the very least, already been seen on TV.

The anxiety that history is at an end, that the present has no alternative, and that the future contains endless reruns of pre-scheduled programming, is reflected in a particular caricature of Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno. The image of the perpetually unamused, ultra-pessimistic Adorno comes from his famous diagnosis of mass media’s alienating effects. “Donald Duck and the unfortunate victim in real life,” Adorno quips, “receive their beatings so that the spectators can accustom themselves to theirs.” And “fun,” Adorno proclaims, “is a medicinal bath which the entertainment industry never ceases to prescribe.”

Thanks, Adorno. No fun.

Just as Fordist production lines stamp out identical consumer goods, the Hollywood industry produces conformity by administering standardized mass consciousness. Free time, scheduled with the same regularity as work time, begins to resemble labour. Viewers ‘clock in’ to watch primetime, are prompted to laugh along with a studio audience, and are regularly reminded to spend their leisure consuming commodities – vehicles, junk food, prescription drugs.

Fast forward to today where media consumers submit to terms and conditions which literally render the passive activity of being entertained into the 24/7 labour of submitting to surveillance and data extraction.

By defining exploitative conditions as entertainment, mass culture tightens the noose around the very possibilities of imagination. Nothing is possible other than what has already been pre-formatted, pre-digested, and pre-screened. In this way, the concept of finding a ‘target audience’ ceases to revolve around marketing a cohesive product. Cultural products are evacuated of any real content in and of themselves. They are disposable means to an end, and culture becomes indistinguishable from advertising.

Just as the mass manufacturing of automobiles produced new social organizations – urban-suburban geography and an emergent middle class – the products of a homogenized ‘culture industry’ collectively produce mass conformity. Every individual can belong to any and every ‘target audience’ when the act of viewing content is implicitly a form of psychological mutilation.

As Adorno argued, to consume culture uncritically in the age of the culture industry is to participate in a collective apologia for society as-is. The mass of homogenized subjects produced in the living room-turned-factory floor are enlisted, against their will and beneath conscious awareness, as guards of the very system that strips them of their freedom. Indeed, it is the idea of freedom and individuality that amputates the subject’s ability to imagine a future beyond the conditions of the present.

Take, for example, the common narrative trope of the underdog. The basic story is that society is an assemblage of bureaucratic overreach and malicious compliance that hinders the true potential of every individual member. In Legally Blonde (2001), for example, stereotypical sorority girl, Elle Woods, is successfully admitted into Harvard Law School against all odds. There, Elle thrives, despite her seemingly incompatible personality, more preoccupied with hair care than case files. In fact, she ultimately solves a murder case by leveraging her unique sorority networking, gaydar, and knowledge of perm maintenance.

The message of the underdog story is fundamentally this: if you are not taken seriously, you’re not the problem, the world is. Whereas Legally Blonde is a Hollywood film, like a Simpsons prediction meme it becomes a retroactive prophecy.

Like Elle Woods, Donald Trump’s transition from entertainment personality to President of the United States is a fairy tale whose moral is authenticity. Just as Elle Woods solves a murder precisely by staying true to her unconventional background, Donald Trump succeeds in politics by sustaining his performance of a no-nonsense businessman as seen on TV for nearly half a century.

The comparison has not gone unnoticed, as TikTok skits make light of Trump’s ‘teen girl’ speech patterns and a 2017 speech from Liberty University has been comedically edited to resemble Elle Woods’ graduation speech. Both are blonde, both are vain, both are funny. Whereas the world offers preconceived notions of lawyers and politicians, both Woods and Trump find unexpected success by refusing to deviate from their personal inclinations as a sorority girl and entertainer respectively.

Yet the underdog affirmation – be true to your inner self, resist external coercion – perversely and maliciously elides the question of where the authentic ‘you’ is located in the first place. As Adorno observed, the aim of the culture industry is to encourage its viewers to be more of what they already are, to resist the change or self-restraint that arises from honest introspection.

What if external coercion didn’t look like disciplinary restraint? What if the license to be free and uninhibited was, perversely, a tactic for capture and bondage? For a subject with no privacy, a subject whose desires and impulses are fully known inside and out, is hardly free.

Turning to Freud, who stands as a fundamental touchstone of Adorno’s analysis, psychoanalytic psychotherapy aims to reveal the ‘truth’ of the subject by bringing unconscious fantasies and impulses to light. Unlike the work of marketing, which also aims to know the consumer better than they known themselves, psychoanalytic self-knowledge entails a confrontation with incompatible wishes, fantasies, and disappointments without succumbing to breakdown.

In other words, the subject ideally recognizes the misalignment between what they want and what they have, and instead of attempting to rectify this lack they learn to live with it. ‘Ordinary unhappiness,’ as Freud called it, is the only alternative to the ‘hysterical misery’ of attempting to neutralize the unsatisfactory nature of reality with an impossible image of perfect happiness.

The culture industry, however, leverages a campaign against the ability to remain unhappy. Real, authentic individuals are like main characters, our screens tell us. Their individuality is rewarded by a perfect Hollywood ending.

As Adorno often stated – riffing off of Frankfurt colleague Leo Lowenthal – the culture industry performs a kind of ‘psychoanalysis in reverse.’ Whereas psychoanalysis aims to fortify the maintenance of a private, unacted-upon fantasy life, the culture industry aims to neutralize any ability to renounce one’s impulses.

To act without reflection is to be ‘based.’ To think without immediate action is to remain an NPC.

Yet, to define authenticity as the unflinching action upon desire is, at once, to be rendered fungible. The culture industry’s high evaluation of the individual and their subjective freedoms enlists that very same individual into alignment with alien desires. Under the promise of a happiness that can be found within, the culture industry ensures that what is found within is the desire to remain inextricably congealed within the mass, to remain transparent, surveillable, extractable, and monetizable.

Even amid the culture industry’s snares, this dispossession does not go unnoticed. It is no surprise that the idea of ‘being yourself’ holds great appeal while the possibility of realizing self-ownership is rendered impossible. Like the irony of Simpsons predictions, to be unapologetically oneself – to be ‘based’ – is just as often a tongue-in-cheek confession of conformity.

Yet out of this brutalization of freedom – in which the subject is stripped of autonomy, imagination, and security – there arises a renewed performance of ownership and value. To have a subjective opinion at all, is to have the ability to own something.

As Adorno observed, it is precisely the most pernicious and pathological of opinions that preserve this feeling of narcissistic ownership. Conspiracy theories, religious ideologies, and paranoically complete worldviews persist precisely because they have no ability to defend themselves against reality. Their purpose, however, is entirely subjective: to demonstrate that one can still think against the grain, that one can, in fact, resist the cold reality in which one can no longer think at all.

Far more viciously than mere ‘fake’ news (as if there were to be ‘real’ news behind a curtain) this situation imposes a voluntary and collaborative mutilation of truth. As Adorno argues, in true Freudian mode, to reduce this mutilation to the pathological deviations of individuals – ‘crazies’ that are not reflective of the majority, so to speak – is to trivialize and misread the nature of the situation. “The undermining of truth by opinion,” he writes, “with all the disaster it entails, is a result of what happened – irresistibly, not as an aberration that might be corrected – to the idea of truth itself.”

In other words, the flattening of the subject – its reduction to merely exposing its insides for every camera, algorithm, and census to capture – is the natural evolution of a quest for truth that increasingly imagines itself to be a task instead of an unending process. Such a vision of truth collapses knowledge into the superficial, the obvious, and the manifest surface – once captured, the data of the world has no potential to produce a world any different than what currently is.

Thus does the rational reduction of the world to mere appearances, to objectivity alone, cancel thought so completely that thought’s only resistance is found in a suicidal rejection of reality. Under such conditions, the kind of critical thinking that might actually addresses the present social conditions seems to be impossible.

Yet, as Peter Gordon has recently argued, despite this seemingly irreconcilable negativity, Adorno’s resistance to producing a cohesive philosophical system or a plan for action was not out of hopelessness. Adorno fixated on the negative precisely because he believed that the presence of hope, the resources for freedom, must be found within an increasingly commodified life to stand against it. Adorno, as Gordon notes, “refused to exempt himself from the society he described.” For the potential for redeeming a corrupt world would be meaningless unless it were located within that very same world.

In a word, Adorno’s assessment of contemporary society is not simply a ‘blackpill.’

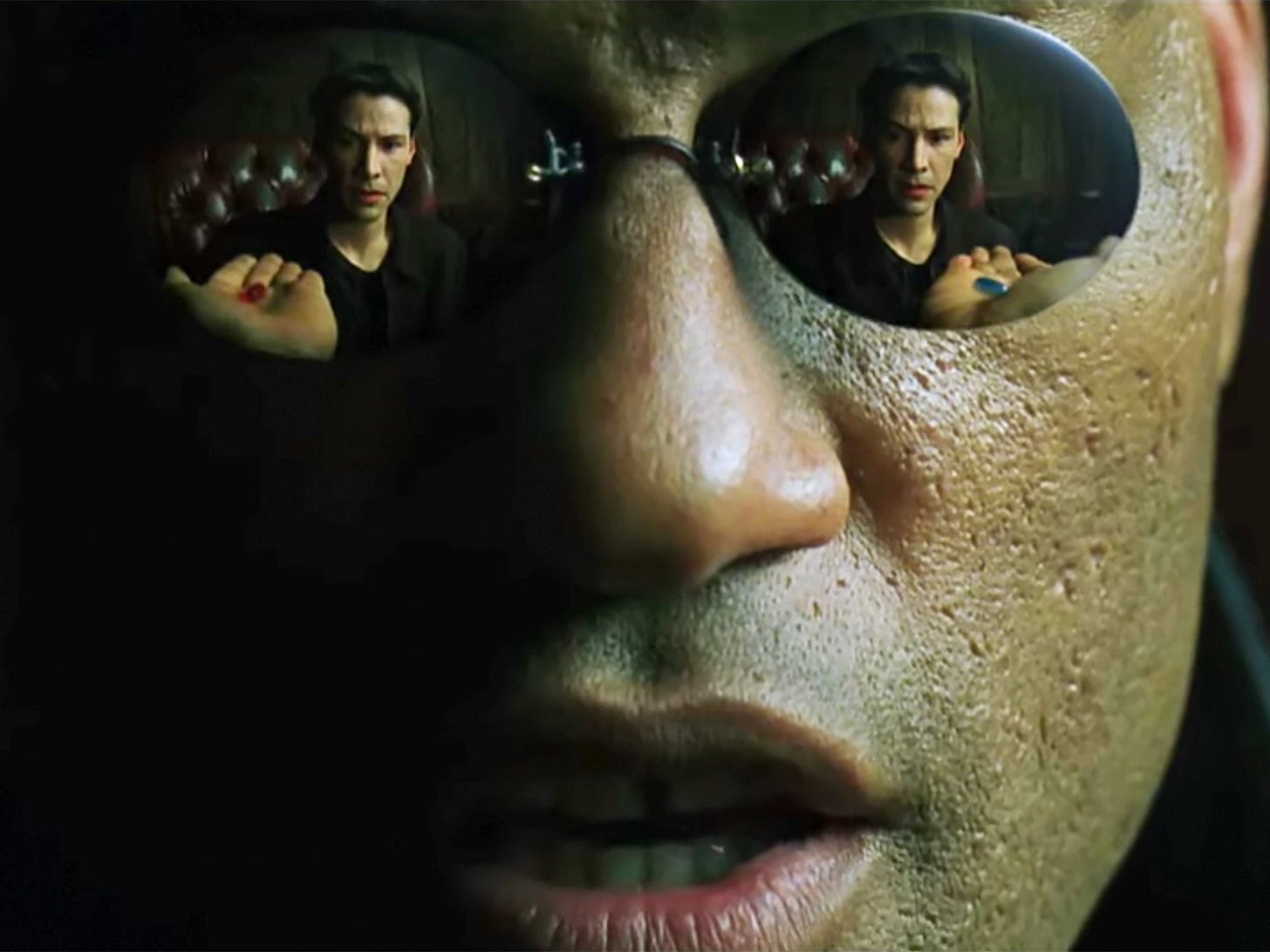

The ‘pill’ analogy famously stems from the Wachowski sisters’ 1999 film, The Matrix where blue pills induce a blissful ignorance, a ‘false consciousness’ of one’s alienation, whereas red pills induce an awakening to the ‘real’ world – to ‘truth.’

Black pills – the result of online, especially incel, culture appropriating the iconography of The Matrix – denote resignation: nihilism. To be blackpilled is to find neither the avoidance nor confrontation with suffering sufficient, for the struggle is futile. In the end, there is no escape from an unfair, dehumanizing, and overwhelming system of control.

Mapping the pill analogy onto Adorno’s critique of society proves the analogy to be deeply unsatisfactory. The strain of hopefulness in Adorno is located in the fact that to speak of alienation at all is to suggest the possibility for autonomous resistance. Likewise, to understand truth as a process of resistance to alienation is to negate the possibility of truth as anything other than an ongoing process with no totality, no end. Truly critical and emancipatory thought, for Adorno, is engaged in the reflection of its own aporias – that is, in unpacking the dense contradiction that forms the dissonance between life as it is lived and life as it might be imagined. If, as Adorno famously wrote, “wrong life cannot be lived rightly,” to confront life’s wrongness is to commit to the possibility of a less wrong life whose rightness may never fully be realized.

Life, for Adorno, radiates with negativity. To reflect upon that negativity is to sift for fragments of a better life that is always currently impossible. Indeed, Adorno, who frequently extolled the virtues of exaggeration, found finality and stasis of any kind – whether resignation or redemption – anathema to critical thinking.

To diagnose contemporary society as a wholly dehumanizing system is a necessary lie through which the cracks in the system’s hold become visible. It is in this sense that Adorno’s pill is a self-negating blackpill. Adorno commits to describing a world so exaggeratedly brutal and dehumanizing, yet so shockingly authentic to our lived experiences, that to merely reflect upon it is to facilitate an impulse towards incremental resistance.

In a world that is so dark, it is exaggeration that dims the lights even further. In so doing, whatever little light remains shines even more brightly.

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor. [1951] 2005. Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life. Trans. E.F.N. Jephcott. London: Verso.

Adorno, Theodor. [1953] 2005. “Television and Ideology” in Critical Models. New York: Columbia University Press. 59-70.

Adorno, Theodor. [1954] 1991. “How to Look at Television” in The Culture Industry. London: Routledge. 158-177.

Adorno, Theodor. [1961] 2005. “Opinion Delusion Society” in Critical Models. New York: Columbia University Press. 105-122.

Breuer, Josef & Sigmund Freud. [1893-1895] 2001. “Studies on Hysteria” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. II. Trans. & ed. James Strachey. London: Vintage.

Gordon, Peter E. 2023. A Precarious Happiness: Adorno and the Sources of Normativity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Horkheimer, Max & Theodor W. Adorno. [1944] 2002. Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. Trans. Edmund Jephcott. Stanford: Stanford University Press.