In Goethe’s well-known poem, “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” a naïve apprentice conjures spirits to assist with menial tasks. Enchanted buckets and brooms perform their work automatically, with no regard to an end. The sorcerer’s tower floods, cast into disarray from an excess of work. The apprentice, however, is unable to remember the old Hexenmeister’s magic words and exorcise the forces animating the inanimate objects of everyday life.

Marx famously compared the forces of industrialization and commodification to that same unyielding magic. Whereas Goethe’s poem ends on a happy, albeit embarrassing, note for the apprentice when the sorcerer returns, Marx understood that some forces are unleashed with no master in sight. Bourgeois society, Marx writes, is increasingly automating and reifying life itself like “the sorcerer, who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.”

Contemporary society is unprepared and increasingly unwilling to acknowledge that our globalized system of commodification and industrialization is at once a marker of progress as well as a ravaging force of dehumanization. Indeed, under the guise of civilization, we are alienated from a potential awareness that the fruits of our labour are rotten to the core. Civilization is made ill by the very force which animated it – an excess of progress, information, leisure, and accumulated wealth.

Human beings are grafted onto the skin of an alien machinery: a program of efficiency and optimization.

This program is both of our own creation and utterly demonic. It entails an autonomous untethering of initially progressive ideals. What was once a magic invoked by human beings in the name of progress, to harness nature and assuage the uncertainty of existence, is now the rote execution of the means with no regard to their ends.

This program is encapsulated in the project of Big Data with its ideals of total social diagnostics through total data surveillance. It is encapsulated in the push towards the replication of the mind in the development of AGI (artificial general intelligence). And this program of efficiency is also encapsulated in the techno-optimistic collaboration between Donald Trump and Elon Musk – especially DOGE, the aptly named and Musk-initiated ‘Department of Government Efficiency.’

Ironically, despite the title of Trump’s reality TV show, both Musk and Trump have only ever been apprentices – in the Goethean and Marxian (and, perhaps, Faustian) sense. The program of efficiency, of course, is the magical force America’s young mages strive and fail to harness. They survey a society possessed by the spirit of reification; a spirit unleased in the name of progress. Unable to bear the uncertainty that persists in spite of the vicious reduction of life to planning and calculation, they imagine their actions – their hand waving and incantation uttering – to control the demonic forces of commodification that flood our tower.

Musk and Trump wade through the water in confident defiance, like pigs waiting calmly at the abattoir. Assured that their butchers are just upright pigs themselves, they are satisfied that somewhere along the way they will have an opportunity to successfully plead their case.

1. Artificial Stupidity

Like many existential narratives, including religion, efficiency for its own sake is a response to an understandable and ubiquitous terror in the face of indeterminacy. One seductive, albeit neurotic, response to this agony is the reconceptualizing of life so that it neatly aligns with a domain humanity has already mastered. The ideal of AGI (artificial general intelligence) is one such effort.

Fundamentally, AGI is impossible. Paradoxically, it is only a matter of time before its arrival. How might this be?

As AI pioneer Hubert Dreyfus argued in the 1970s, the optimistic pursuit of creating an artificial mind had thoroughly collapsed into a new paradigm of neural network modelling. That is, the pursuit of synthetic consciousness transitioned to the automation of mathematics. As recent development in AI clearly demonstrates, the ideals of AGI have not been revived. Popular conceptions of AI as comparable to the workings of the human mind merely reconfigure our understanding of what the human mind is able to do.

As Dreyfus pointed out, the fundamental problem is that it is easier to synthesize the functioning of brain biology than consciousness. AI innovations, such as large language models, take the basic functioning of the brain – building indexical connections from out of vast swaths of data – and multiply it beyond recognizability as brain functioning. Human minds do not operate through the brute force method of compiling all information accessed by the senses into a complete phone book of experience, the entirety of which is logically parsed through and assessed with each cognitive operation.

This, however, is precisely how AI produces novel content. It recognizes patterns in training data, reduced to the smallest possible units, which inform a predictive calculation that remixes and recombines training data in response to external requests. Operating along these basic lines, AI has long abandoned any attempts at emulating the context-dependent capacities for novelty which form the basis of human intelligence – of consciousness.

Just as Soviet Bloc countries satisfied themselves with an ‘actually existing Socialism’ that would point to the (failed) promise of ideal socialist societies, AI research has satisfied itself with a kind of ‘actually existing AI’ that points towards a potential AI of the future. The state of AI is like a toy model of the brain, infinitely enlarged and amplified in the hopes that its brute-force expansion might lead somewhere new.

The paradox that AGI is impossible yet inevitably will come into existence, is resolved when one recognizes that artificial intelligence will cease to be impossible once the meaning of human intelligence is sufficiently altered. The possibilities for imagining what the human mind is capable of, need only be reduced to match the limits of what predictive computation is able to accomplish.

As a result, AGI will not be invented, since once it arrives it will have already been in existence. AGI will be begotten out of the auto-amputation of human intelligence to mere indexicality.

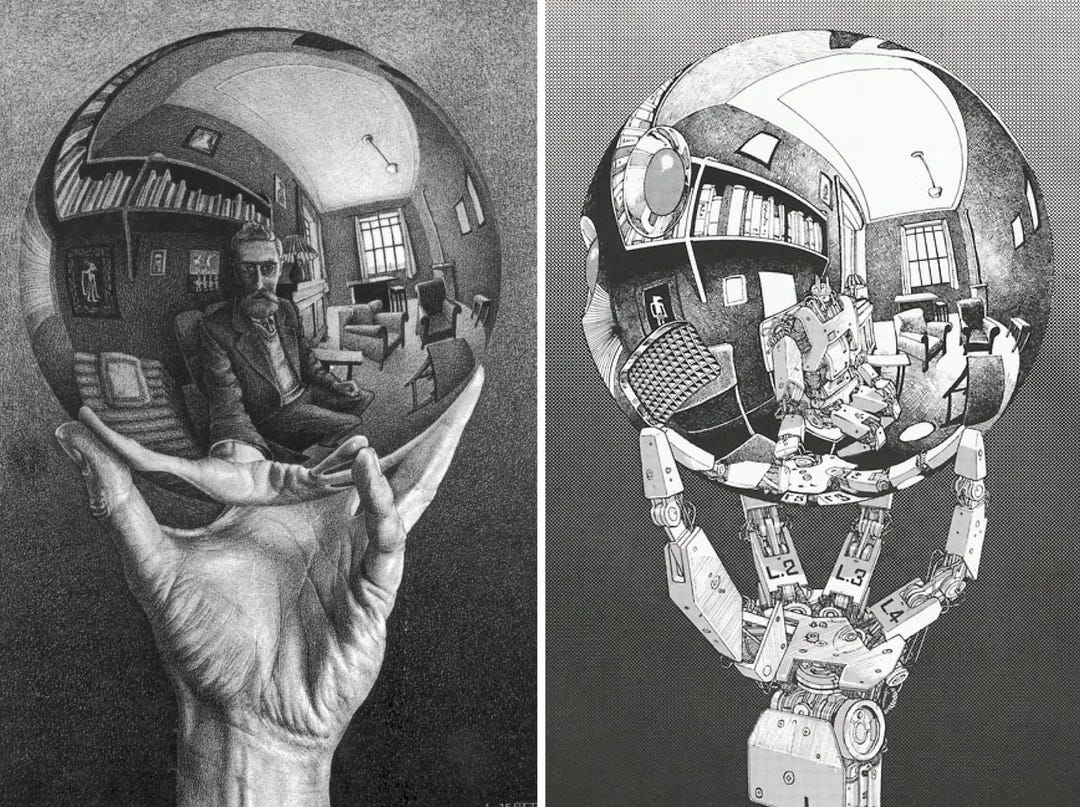

As McLuhan contended, human beings are the sexual organs of the machine world. Our prosthetic limbs reorganize the world in such a way that the originals are altered. In the hands of busy-bee humans, the wheel makes the organic leg insufficient, the radio makes the organic ear woefully inadequate at hearing. A famous McLuhanism is that the cowboy becomes the servomechanism of his horse, the CEO becomes the servomechanism of his clock.

Similarly, with AI, the prosthesis amputates the original. The amplification of one type of calculating, indexical cognition produces a world which demands the eradication of alternate potentials for thought.

The distinct difference between leg and mind, however, is that AI is a prosthesis of being itself.

The prostheticization of mind is an attempt to preserve subjectivity through the production of an artificial subject. AI strives to ease the terror of temporal existence precisely through the promise of immortality – the materialization of the soul through the reduplication of the subject.

Within the increasing dehumanizing of late capitalist society, the anxiety that demands salvation reaches an intolerable level. The success of the wheel demanded a servomechanical relationship with our mode of transportation, stretching the leg beyond its organic means. Conversely, the failure of AI demands an amputation of our excess organic intelligence, a servomechanical relationship to a limited intelligence of our own creation which increasingly shapes the world in a manner that rejects any form of intelligence beyond its limits.

AGI and the ideal of replicating and preserving the human subject is achieved by instituting a world governed by calculating efficiency, a world which gradually demands the reduction and reformulation of what it means to be human.

Salvation is at hand, so long as what ought to be saved is sacrificed.

2. Heil, Robot

It is wholly unsurprising that, across the board, contemporary politics is concerned with eradicating the critical study of culture. This is a bipartisan project which transcends the traditional political spectrum. It is governed by the demand for culling the messy nature of thinking down to a level already matched by computational efficiency.

Among left-leaning institutions, including very many universities, this assault on thinking takes the form of a kind of self-castrating, equity-driven refusal to partake in impartial, truly ruthless criticism. Among right-leaning institutions, including DOGE, the assault on thought takes the form of a downright eradication of the humanities as a set of disciplines.

The unifying tendency is the assurance of binary, categorical truth – good and bad, one and zero – and the attempt to execute this ‘truth.exe’ program across all systems of society. As a result, seemingly opposed political perspectives have found themselves horseshoed towards an identical position: central planning in the name of efficient management.

Indeed, in the 1940s, economist and philosopher F.A. Hayek’s analysis found both fascism and socialism to coalesce upon the singular ideal of centralized planning. As he wrote, the organization of progress is a contradiction in terms that mistakenly analogizes the impersonal results of progress with the personal force of reason. Just as the idea of what an artificial intelligence ought to be ends up reformulating the terms of what a human intelligence is, the attempt to produce a collective, rational guideline for society is an attempt to formalize reason. As Hayek noted, “by attempting to control [reason], we are merely setting bounds to its development and must sooner or later produce a stagnation of thought and a decline of reason.” A form that this takes is, of course, the ‘paradox of collectivism,’ as Hayek called it, in which the demand for a conscious, complete, and rational plan for society inevitably leads to the demand that a particular individual or category of identity stand above and master the overall collective.

Today, we are faced with an eradication of the individual – the unit which Hayek sees as necessary in recognizing the superindividual forces, as he puts it, which guide the rational management of a society. Given enough time and enough instability, late capitalism, itself, collapses into the same collectivist forces of risk-averse efficiency that marked the explosive development of socialism and fascism over the last two centuries.

The emphasis on efficient management, propped up by Trump and Musk, is a single example of an otherwise ubiquitous and bipartisan assault against thinking. This assault is far from irrational, it is the logical result of a formalized measure of progress. The measure of machinic efficiency has been both widely accepted as a central plan for civilization, while simultaneously exposing its increasing unfeasibility. As a result, the plan is incapable of being abandoned. It is humanity itself – or, rather, a historical conception of the human subject, of thought, and of reason – which will have to be abandoned in its stead. We are all complicit in a system that will ensure what we currently call thinking is unimaginable to future generations.

Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno was astute in his observation that “technology is making gestures precise and brutal, and with them men. [Technology] expels from movements all hesitation, deliberation, stability.”

For Adorno, the obsessive cult of efficiency produces “technological people.” They function, more so than live – the patterns of working on the factory floor, replicated in the patterns of leisure in front of the television. Both acting as assembly lines for future functioning, more so than sites of novelty and creation. As a result, cognition is reduced to an engine idling on the spot. The subject’s determinations, beliefs, and opinions about the world consistently defer to the measure of efficiency. All thinking produces more thinking for its own sake – thinking as coloring inside administered lines, thinking as mere thinking inside the box.

We have a tendency, for Adorno as well as for McLuhan, to mystify technology – to promulgate it, spread its seed ‘as-is,’ without consideration for the fact that technology is not an autonomously progressive force. Technology is the collaborative result of human actions, insecurities, and wishes. Mystifying technology as a guiding force that rises above and administers guidance to the collective mass of humanity produces a reified consciousness, one that yokes life itself to an alien logic of calculated efficiency.

As Hayek aptly wrote, “the effect of the people's agreeing that there must be central planning, without agreeing on the ends, will be rather as if a group of people were to commit themselves to take a journey together without agreeing where they want to go: with the result that they may all have to make a journey which most of them do not want to all.” Efficiency is just such an agreement, an agreement of guiding principles with no regards to the various mutilations of individual and social life that the journey would entail.

Adorno would not be surprised that fascism, today, becomes a tongue-in-cheek topic among technological optimists and efficiency cultists. As the logic goes, if social media platforms such as Twitter optimize communication by targeting algorithmic models of user desires, all information must be evacuated of content – information ought to be mere bits and bytes of data which can be tracked and traced in measuring the efficiency of a system of unyielding info-consumption. Musk’s plausibly deniable Sieg Heil at Trump’s inauguration was not, in this sense, a proclamation of Nazism or racism of any sort, but a sly nod – along with his ‘Dark MAGA’ leanings – to the fact that Twitter is a system which does not let something as ‘backwards’ as offense impede the progress of efficiency.

As the ensuing plethora of ‘my heart goes out to you’ jokes demonstrate, Musk and his supporters mimic authentic fascism, not because they are all fascists, but because they are invested in modelling society off of the lubricated idling of thought, off of the postmodern evacuation of signification that would facilitate the success of communication platforms – all signal, no noise. No information, either.

Perversely, the commitment to eradicating offense optimizes thinking in the same way that the commitment to assuring offense does. In this sense, total deregulation and total censorship operate alongside identical trajectories. Both seek to flatten and measure the success of human experience according to a calculable and mathematical model, in the same way that synthetic intelligence begets itself, not from technological novelty, but from a reduced organic intelligence that redefines its own limits.

As Adorno wrote, “the movements machines demand of their users already have the violent, hard-hitting, unresting jerkiness of Fascist maltreatment.” And it is in this sense that proclaiming Musk to be a Nazi is as fascistic a maneuver as Musk’s own Sieg Heil. Musk is no Nazi, but he is as fascistic as we are all becoming – a vanguard in the eradication of thinking in favour of idling on the spot, the institution of repetitive efficiency over the contradictory work of novel achievement.

In the name of efficiency and optimization, human intelligence is dismantled in order to conform to the limits of an artificial intelligence – humanity is cut down in order to meet the expectations of its insufficient, technological double.

This is the collective project of both the liberalism which Musk and Trump deride, as well as the conservatism they uphold. The fundamental difference between political positions is eradicated as both conform to a unified authoritarianism – the collective plan of the machine.

Today, both ends of the traditional political spectrum market themselves in unison:

Life is all wrong. But we have assessed all debits and credits, we know who is overdue and to what amount, and if you execute our program exactly, across all systems, we can make life right again.

But as Adorno wrote, “wrong life cannot be lived rightly.”

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor. 2005 [1951]. Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life. Trans. E.F.N. Jephcott. London: Verso.

Adorno, Theodor. 2005 [1961]. “Opinion Delusion Society” in Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords. Trans. Henry W. Pickford. New York: Columbia University Press. 105-122.

Adorno, Theodor. 2005 [1967]. “Education After Auschwitz” in Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords. Trans. Henry W. Pickford. New York: Columbia University Press. 191-204.

Dreyfus, Hubert L. [1972] 1992. What Computers Still Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason. 2nd. Rev. ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Hayek, F.A. 2007 [1944]. The Road to Serfdom. Ed. Bruce Caldwell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marx, Karl & Friedrich Engels. 1972 [1848]. “The Communist Manifesto” in The Marx-Engels Reader, Ed. Robert C. Tucker. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 331-362.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: Signet.