If Jesus Was a Pornstar

Stars and Monsters in Ti West's "X" Trilogy

“In this business, until you're known as a monster you're not a star.” - Bette Davis

Both pornography and horror suggest that authentic revelations – visions of truth – require a transgression of the visible. Both pornography and horror peer into human insides by stretching, excavating, and tearing into the seemingly stable human subject.

Both pornography and horror reveal life by snuffing it out. That is, they subject life to the rigid classification and unyielding scrutiny of cinematic capture.

A third category, however, offers a similar revelation of otherwise invisible human insides: the sacred. And it is the interplay between the three categories (of pornography, horror, and the sacred) which is explored in Ti West’s recent trilogy of films: X (2022), Pearl (2022), and MaXXXine (2024).

1. Cinema’s Hard Core

X, itself, is a post-mortem.

Nestled between two segments in which police officers comb through a brutal crime scene, the evidence tape they find is “one goddamn, fucked-up horror picture.” It is the result of bodies which have collided and been captured, in the totality of all their parts, by a machine. Like the body of the unfortunate cow that meets a transport truck, the human body is seized inside and out as it meets (meats?) the camera lens.

The film follows Maxine Minx (Mia Goth) who, with a small crew of adult performers and filmmakers, sets out to capitalize on the growing home video market by shooting an amateur adult film. While most of the crew are in it for the quick money, Maxine dreams of stardom. The group rents out a house on the property of an elderly couple, Howard and Pearl (Goth, again, prosthetically aged).

As we find out in Pearl, Howard has been assisting Pearl in covering up a lifetime of murderous sexual violence stemming from her failed attempt at becoming a film star in the 1910s. While Howard warns the film crew to stay away from their house so as not to bother his wife, Pearl seems to want attention and is aroused by spying on the crew as they shoot their adult scenes. Her voyeurism, however, turns violent and Pearl brutally murders the film crew.

Unlike Pearl, Maxine, who survives the slaughter, does make it to Hollywood in MaXXXine. Her religious father, however, is on her trail. Leading a camera-obsessed cult, he replicates the perceived filth of Hollywood, ritualizing murders and atrocities in front of his handy-cam in order to condemn them.

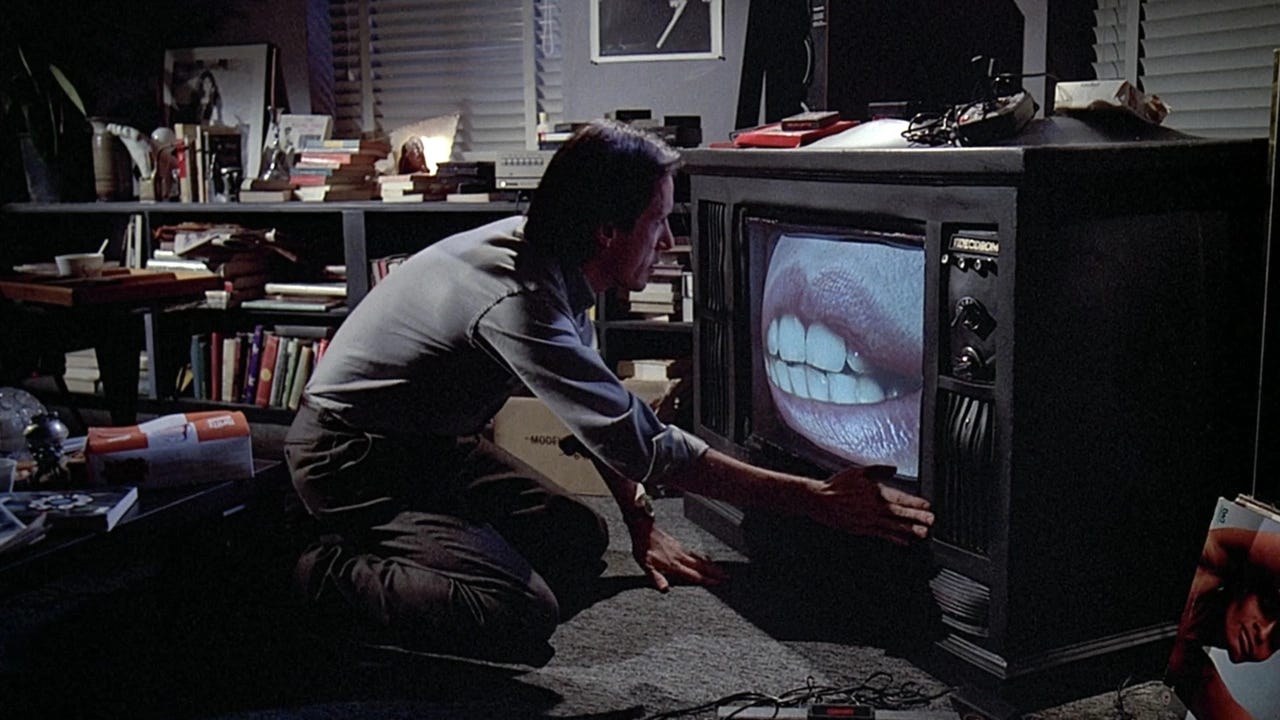

We first meet Maxine’s father in X, where a screen within a screen punctuates several crucial scenes. The televised preacher, who we ultimately learn is Maxine’s estranged father, utilizes her image as a runaway tempted by Satan to seduce spectators. Using the image of innocence, he draws spectators into a world of sordid sex and violence even as he condemns it – not unlike the pulsating TV set which frames Debbie Harry’s lips in Cronenberg’s Videodrome.

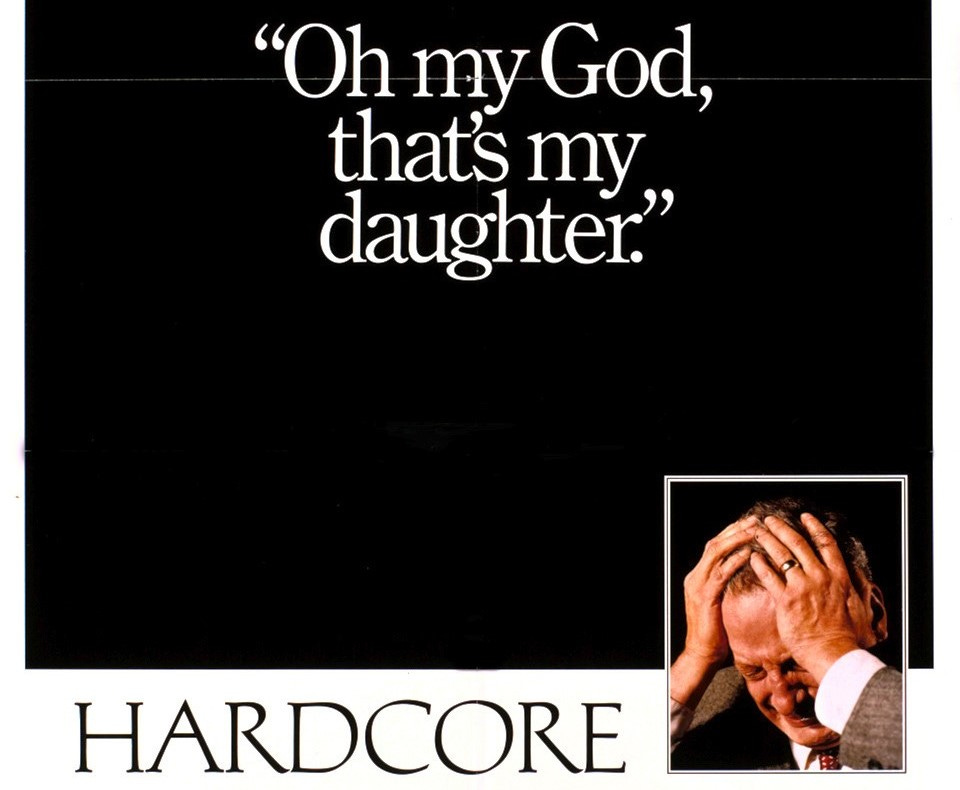

The role of Maxine’s father pays homage to Paul Schrader’s classic Hardcore (1979), which also features a religious father in search of his runaway daughter. In both MaXXXine and Hardcore a figure of order and classification must participate in the seedy underbelly of society which has destabilized his reality. To restabilize he must come to know – categorize, classify, and, indeed, internalize – the antithesis of his existence.

In Hardcore, for instance, the father searches for his daughter among Los Angeles’ sex workers, posing as the exact kind of person he would rather she not meet: a sleazy adult film producer. In MaXXXine, the father in search of his daughter replicates the violence and sexual depravity he seeks to condemn.

West’s trilogy alludes to an equivalence between the ideals of vigilante father and runaway daughter – between the religious and the pornographic. Both are driven by a neurotic compulsion to attain a sense of certainty – to become as eternal as stars. Both strive to attract the masses, at any cost, by revealing, unveiling, and exposing a previously unseen hard core embedded within the human experience.

2. Fucking Religion

Maxine ultimately achieves her stardom when she overcomes her serial-killing father in MaXXXine. His role, as a punitive, Old Testament God who is meant to be overcome, reinforces the Christ-narrative first hinted at by the wooden boards featured on the promotional material for X.

In MaXXXine, she is “almost thirty-three” – the same age as Christ when he was crucified. In her attempt to break into the mainstream film industry, she makes the leap from pornography into horror – the same leap Christ made from beatitude to mortification.

Just as Christ’s passion – the stretching of his body beyond its final limit – is ultimately a celebration of human redemption, Maxine’s passions, screened in seedy cinemas and the ‘true crime’ news cycle, are a beatific crucifixion.

Although Pearl, like Maxine, demanded stardom, all she received was a life of private suffering. Maxine, however, operates in a new age where public consumption is increasingly dependent on private production. An age where authenticity is, itself, the manufactured product. By the 1980s the camera was about to blossom into that penetrative organ of revelation which would only be further normalized in the coming era of salacious reality television, confrontational talk shows such as Jerry Springer, and, eventually, viral user-generated content. Unlike for Pearl, Maxine is dealing with a media environment where private suffering can be synonymous with stardom.

Indeed, like a celluloid Christ of female rage, Maxine comes to bear the burden of Pearl’s sins – replayable, ad infinitum, in the VHS-tape of her memory. But Pearl’s murders, just like Maxine’s father’s murders, have always been physical media objects as well – police evidence tapes that can be distributed as objective, reified proof of Satanic evil.

Christ, too, was always a figure of mediation and monstration, occupying a liminal space of transmitting and showing one realm and another. Christ was a monster, precisely because he de-monstrated what he obscured. That is, Christ obscured full knowledge of a transcendent beyond through his humanity, while also drawing our attention to this beyond through his divinity.

Maxine, too, achieves immortalized stardom through violence and mortification thanks to the guiding hand of Her father. Like Jesus, Maxine is a monster in order to be a star – she demonstrates a shattering of old categories of humanity, old models of being.

And this shattering is also a salvation. As the tagline for X states, Jesus is “dying to show you a good time.”

Religious violence, in this way, rationalizes and harnesses an out-of-control brutality that undergirds the human experience. Religious violence is a defence against, as well as a release valve that indulges and legitimizes an incomprehensible horror inherent to humanity by ejecting it into the realm of the sacred. And in this sense, it is coherent that Maxine’s religious father condemns the horrors of violence by manufacturing them, replicating them, and distributing them for the world to see.

For both Maxine and her father, the production of images of bodies stretched to their limits – in sex and death – is a redemptive act that saves humanity. Just as when Maxine was a child, being promised a life of stardom, she remains in front of the camera and he, behind it – embodying the camera, internalized as a bio-mechanical amplification of his own ocular perspective.

3. What’s Inside a Girl?

From Golden Age of Porn hits such as Deep Throat (1974) to the gonzo escapades of Rocco Siffredi, pornography, as a category of cinema, emphasizes the camera’s ability to raw-dog reality. Pornography asserts itself as a kind of x-ray vision of the human – especially female – subject.

The subjective and invisible realities of sexual arousal frustrate cinema’s ideal of capturing and cataloguing human experience, and Deep Throat literalizes this frustration by relocating Linda Lovelace’s clitoris deep within her throat. Although the clitoris has been eradicated from view, highly volatile, explosive, and cinematic objects, such as the gigantic dissapearing/returning penis, rockets, fireworks, and ringing bells, all stand in for the invisible reality of the female orgasm.

By the 1990s, pornography would adopt a far less symbolic tactic. The newly compact camera, in the hands of performers themselves, would become less an instrument of sexual excavation, as an auxiliary organ welded to the body. The camera, shrunken down in size so as to follow the path of natural vision, realizes the impossible desire to look through the phallus – another one-eyed (de)monster(ator).

And it is the camera – the monstrating apparatus – which offers a redemptive hope, the ability to save the fleeting scraps of life. As Edgar Morin recognized, in 1954, “photography was already the chemical Saint John the Baptist for a cinematograph that delivered the image from its chains.” That is, cinema has the potential to harness the calculating capture of physical reality afforded by the scientific apparatus of the camera, while balancing this capture with a transcendent and transformative revelation of what was never visible in front of the lens to begin with.

Cinema can manifest the invisible realities which permeate human existence. And it can do so through techniques which anchor the invisible to the visible which is framed by the screen.

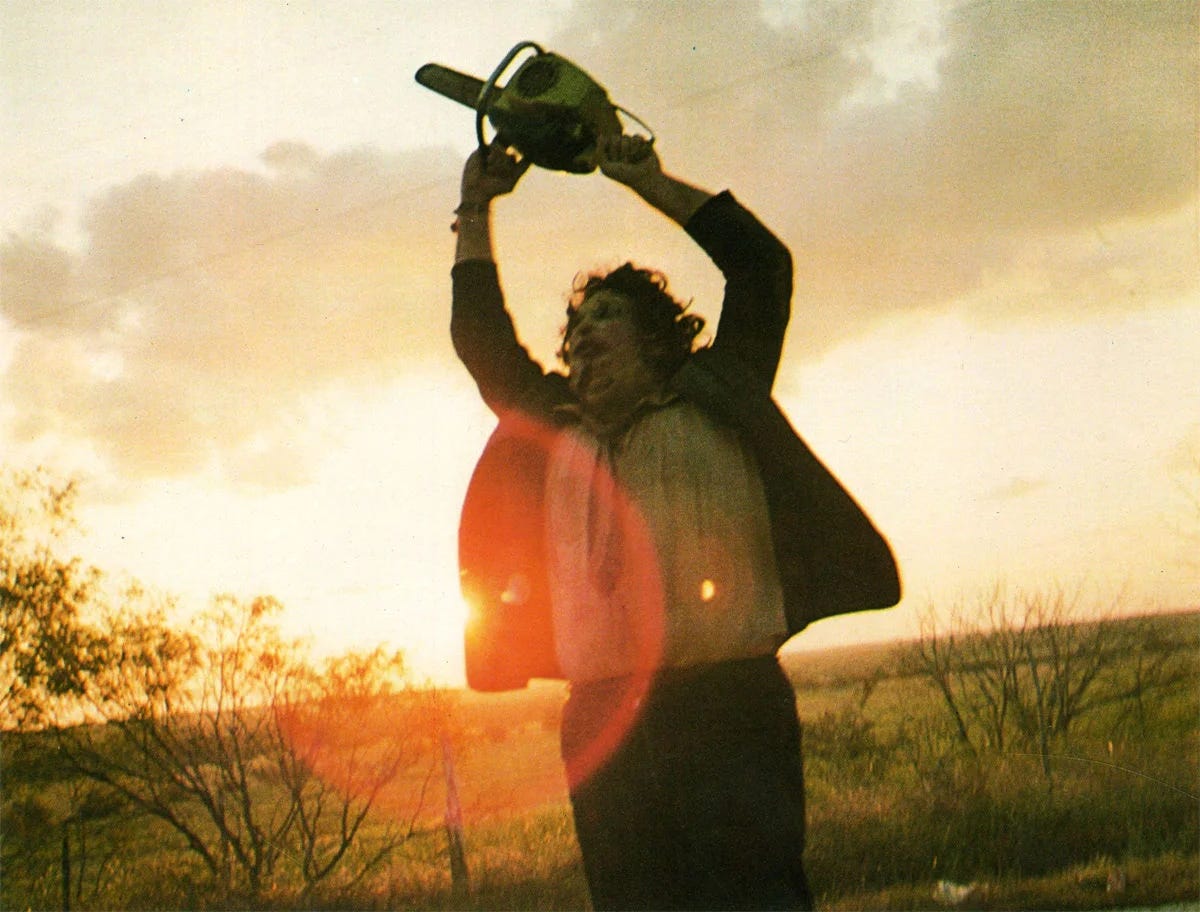

Horror, too, leverages tactics of authenticity such as the intentional misinformation (“the film you are about to see is true”) of classics such as Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974).

In Hooper’s seminal film – interestingly funded by the same mafia-backed production company that got its start with the similarly seminal Deep Throat – we find a family of out-of-work slaughterhouse employees reverting to what they do best. Beneath the idyllic veneer of the American countryside, is the brutal overextension of society’s rational imperative to do one’s work – regardless of whether that work is done upon cattle or young men and women.

West’s films, with the homicidal repressions of both Pearl and Maxine’s devout father, evoke Texas Chain Saw’s desublimation of socially regulated and sanctioned desires. Whereas the young bodies of the porn performers are given societal license to express their libidinal urges, they may only do so within the narrow confines of socially acceptable sexuality – the limited, normative sexuality of the pornographic imaginary. Pearl, on the other hand, is possessed by those same desires. Yet incapable of finding a safe, socially sanctioned outlet, the impulse to domination, the aggression and violence which bubble beneath the surface of human sexuality, is left uncontained.

A common criticism of X suggests a tendency to demonize the elderly. However, Pearl’s backstory highlights the terror, not of bodies which fail, but of bodies which retain their libidinal charge. Pearl, as a monstrous figure in X, is terrifying not because she is old and frail. Pearl is monstrous because she draws attention to the socially unacceptable reality that failing bodies will not necessarily house failing desires – they, too, will strive to mimic the well-oiled bodies in motion of pornography’s fantasy-scape. In this sense, the terror is, perhaps, just as much the perennial youth of cinematic ideals, tasked with excising scraps of life in order to pin them down like petrified insects.

4. From Paintbrush to Camera to Chainsaw

Walter Benjamin presents a well-known analysis of the photographic image as lacking an aura that was retained in painting. What is lost in the photograph’s reproducibility is ‘something more,’ something which adds to the otherwise static image, functionally melding it with human life outside of its frame. Whereas the painter, Benjamin argues, is like the magician – at a distance from the reality which he is dealing with, producing it out of the unique interplay of plastic media and imagination – the photographer is like a surgeon cutting into and extricating a slice of life with the opening and closing of the shutter. A third figure, however, emerges as we consider the pornographic and horrific images commented on by West’s trilogy.

The artist as killer.

There is a classic killer point-of-view which gained popularity in the giallo genre, persists though to today’s found footage films, and is cited repeatedly by Maxine’s father’s murder tapes. In this framing of murder, leather-gloved hands are poised to strike, seemingly extending from the spectators themselves to throttle the life out of the images onscreen.

Unlike the therapeutic work of the magician and the surgeon, the killer comes to preserve and to know physical reality in a way which is antithetical to life. But the killer is also a figure which returns a ritualistic aura which the surgeon lacks. The killer resists sameness and replication through the interruption and desecration of life. Instead of offering an aesthetic for creating and sustaining the masses, for administering ideas and foreclosing autonomous thinking, the killer offers a ritualized form of social transformation.

So, at least, Maxine’s father envisioned.

And in order to demonize the world of Hollywood, Maxine’s father manufactured its demonic aspects. So, too, Christ’s mortification is a divinely engineered violence, a sacrifice that takes on the burden and pornographically reveals a violent world in order to redeem it. Maxine’s role in halting her father’s murder spree, herself committing a televised patricide, is a transgression in the sense of Georges Bataille’s conception of eroticism – a union of the erotic and sacred. As he wrote, both sex and sacrifice “reveal the flesh. Sacrifice replaces the ordered life of the animal with a blind convulsion of its organs. So also with the erotic convulsion; it gives free rein to extravagant organs whose blind activity goes on beyond the considered will of the lovers.”

Such a transgression breaks the mold of established limits without totally destabilizing the world. Like Jesus’ mangled body represented a monstrous new man that shattered the norms of antiquity, Maxine is the new woman who sacrifices herself at the hands of the media’s killer gaze and in so doing breaks through to new forms of freedom as well as new norms of regulation and control.

Ultimately, the camera is that monster-machine which transmutes fragile human bodies into an eternal substance. The camera records and preserves, though not without abstraction. It geometrically and rationally deconstructs the flow of life into its component parts – a crucifixion, a killer image.

As we see in both Schrader’s Hardcore and West’s MaXXXine, to capture and stabilize one’s reality requires a descensus just as much as an ascensio.

In addition to Hardcore, MaXXXine is comparable to another, and arguably greater, porno-noir classic – Fred Olen Ray’s Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers (1988). Significantly, Ray’s film marks the onscreen return of Gunnar Hansen – over a decade after his appearance as the original Leatherface in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

In Ray’s film, Hansen plays the Stranger: a foreign, chainsaw-worshipping cultist leading a group of human-sacrificing hookers. In Hansen’s initial role, as Leatherface, industrialized social activity is desublimated back to an originary impulse for industrialized murder – the monster, horrifically, is the realization that the inner, American family is merely wearing a human face with nothing resembling humanity beneath it. As the Stranger, Hansen’s role is inverted to an equally extreme form of sublimation – the horror of barbarism is encountered, not beneath the crumbling veneer of humanity, but through an overwhelming excess of organization and order exemplified by the unyielding recourse to repetitive religious sacrifice.

The film follows a private detective who, like in MaXXXine and Hardcore, is searching for a teen runaway among sex workers in Los Angeles. He finds the girl, but his search leads to an underground cult of Hollywood chainsaw hookers. As he humorously ponders to himself, “I had to wonder if we’d let our religious freedom go too far in this country.”

Perhaps that’s precisely the polarity between Hansen’s role as Leatherface and the Stranger. In one role, he depicts the base desublimation of socialization – the impulse to do one’s work as arising from an impulse towards aggression and violence, only to collapse back into mechanical butchery of human bodies. In the other role, he depicts the repressively illusory sublimation of religious order – human violence is now neither an uncontrollable social aggression, nor social work, but the surplus expenditure and ritualization of that same violence into a transcendent frame of the gods. The Stranger is, in this sense, an ascended Leatherface who had always had the potential to turn his chainsaw, as a machine of division, into a cosmos-organizing apparatus. The camera, from the killer’s perspective, is the apparatus of division and capture – a machine that butchers in order to preserve, that rends the present moment asunder in order to catalogue it for all eternity.

And as Bataille observed in 1929, Hollywood is akin to a contemporary pilgrimage site – a holy place which fulfills the same religious function as a temple. The senselessness, banality, and absurdity of human experience requires dreams, and it is Hollywood as the dream machine where life can once again be made bearable.

Hollywood is the only place in the world that can generate the same kind of seductive illusions that religion once did. It is the only place where violence can be ritualized in a way that preserves its fundamental presence at the core of humanity, while also protecting us from the effects of everyday violence. Hollywood is a sacrificial release valve, full of yesterday’s monsters and gods in the form of today’s film starlets.

Bibliography

Bataille, Georges. [1929] 1970. “Lieux de pèlerinage Hollywood” in Oeuvres complètes I: Premiers écrits 1922-1940. Paris: Gallimard. 198-199.

Bataille, Georges. [1957] 1986. Erotism: Death & Sensuality. Trans. Mary Dalwood. San Francisco: City Lights Books.

Freud, Sigmund. [1907] 2001. “Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Trans. & ed. James Strachey. London: Vintage. 117-127.

Girard, René. [1972] 2013. Violence and the Sacred. Trans. Patrick Gregory. London: Bloomsbury.

Morin, Edgar. [1956] 2005. The Cinema, or The Imaginary Man. Trans. Lorraine Mortimer. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Filmography

Damiano, Gerard [Jerry Gerard]. 1972. Deep Throat. New York: Bryanston Pictures.

Hooper, Tobe. 1974. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. New York: Bryanston Pictures.

Ray, Fred Olen. 1988. Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers. Camp Motion Pictures.

Schrader, Paul. 1979. Hardcore. Culver City: Columbia Pictures.

West, Ti. 2022. X. New York: A24.

West, Ti. 2022. Pearl. New York: A24.

West, Ti. 2024. MaXXXine. New York: A24.