Bumpin' That

Media, Art, and Brat Politics

As early as 1972, Jean Baudrillard lamented the death of media.

But even he was late. Media have never mediated.

Media have never been neutral channels of information. From the scroll, which asserted authorial integrity, to the loose-leaf codex, which invited editorial rearrangement, to the online interaction…

Media have always dictated the patterns by which information is disseminated and received, to the point that information, as a stable concept, is a figment of our imaginations.

All public information is uninstructive disinformation. It is the process of transmission, itself, which instructs – or rather, coerces. “The medium is the message,” as McLuhan said, and only those who instate forms of ubiquitous media are able to speak. Mere users remain silent.

Our media devices speak for us, for any reply we might have falls on deaf ears. The naïve notion that information is power, that media can be emancipatory if used ‘correctly,’ is a virulent myth. The use of media, no matter by whom, presupposes a vested interest in obscuring the fact that all information is an interchangeable blank. The mythic ideal of responsible mediation only dissimulates the coercive impulse to increasingly transform human beings into manageable, machine-like resources, by coercing them to internalize the processing patterns of information machines.

It thus follows, as Baudrillard aptly noted, that we are certainly not in short supply of meaning. Meaning is everywhere, and it is produced today at breakneck speeds. But meaning doesn’t mean anything unless it responds to a public’s demand. If the demand for meaning wanes, the coercive hold of mediation is broken – for why would anyone listen?

“kamala IS brat.”

Politics is incoherent entertainment. It means nothing, but it multiplies the desire for continuous participation.

Politics is an aesthetic, an idea, a marketable aura disconnected from the mundane realities of daily life. Politics is a Tumblr aesthetic, a Spotify playlist. Politics is scheduled for leisure, and leisure alone. Political participation is voluntary, like streaming, scrolling, and surfing the web.

But beneath the veneer of elective political engagement is a justification for the real politics which remains invisible, non-participatory, and mandatory – a politics to which we are unwitting victims during ‘working hours’ so long as pop-political spectacles occupy our ‘free time.’

Indeed, the preoccupation with universes that house recurring characters and tropes – the Marvel Universe, the Harry Potter Universe, the Star Wars Universe, or even the Universe of American Politics – is a symptom of various tactics for eliciting participation, inviting spectators and users into auxiliary worlds of meaningful activity where they can electively live.

Or rather, the masses do not live there, they decompose. They inhabit virtual, disposable cosmoses. Happily moving from one to the other, the masses support a system which perversely creates infinite worlds in order to hide one from the masses.

Taylor Swift’s universes, for example – each an ‘era’ unto itself – are lofty resting place for the decomposition of today’s teen psyche. Each album invites repeated listening, a sense of community on social media platforms, and habitual mediation between Swifties, haters, and the general population.

No more autonomous thinking. Just clever wordplay, addictively scheduled merch drops, content releases, and the assurance that, although it will all evaporate into vacuity with the next world-update, the next world-update will come with no effort on our part. Instead of painfully negotiating social existence, instead of scaffolding a contradictory world into something which might be better – more emancipatory, less oppressive, more inclusive – than what came before, worlds themselves are scrapped and rebuilt. And when production slows, the same world can be created once again, but this time… (Taylor’s Version).

It’s cheaper to trash and rebuild everything, than to negotiate the contradictions of targeted updates. This is also why every device on the planet – every laptop, iPhone, and, even, modern car – is destined for the landfill within a decade.

Reuse, reduce, recycle becomes the mantra of human life, as well as consumer commodities.

Charli XCX’s Brat, like so much curatorially rough-edged and indie-infused pop, initially seems to be an instance of commodified culture rejecting its rigid and reified nature. To be brat is to refuse to speak. Unlike Swift’s tortured poets, who are painfully verbose, brat does not overshare its identity. It seems to affirm a negative identity at every turn.

What is brat?

Brat is contradiction, brat is emotional and callous, composed and breaking down, elated and depressed.

But the negativity is a façade. Brat is an ephemeral cultural update like any other. Brat bulldozes contradiction by feigning contradiction. Its image is that of ambiguity, but it invites participation in yet another mass media universe at the brink of collapse and re-release.

A new world that is perpetually the same, yet perpetually different, so it’s not.

All art is political. No matter how staunchly it feigns autonomy (art for its own sake), all art bears forth unstated implications of its place and its time.

Perhaps most importantly, all art advocates for its own medium.

This, in and of itself, is a radical political statement. All art has a hand in shaping collective social consciousness by being mediated (McLuhan’s “medium is the message”). Hence, today, no matter how staunchly art asserts its commitment (art with a message), it works in the service of a dehumanizing and authoritarian medium.

This is not, of course, to say that Brat is bad art. But it is to say that the concept of brat was already deeply political, far before it memed its city-sewer-slut vibe into the Harris campaign.

To be brat – as a construct that promotes contradictory silence, an ‘it is what it is’ mentality, where life is the party that entertains you to death – is to align oneself with a particular political identity.

As Adorno argued, all art, like politics, is an argument for the world to be otherwise. But in the context of an industry in which the production of disposable participation is an end in itself, the world that art argues for is a dead world that clings to the shadow of life.

Instead of producing an imperfect social world through participation, the social updates itself wholesale, passively, without our engagement or consent – like software that registers optimal down-time to perform its updates.

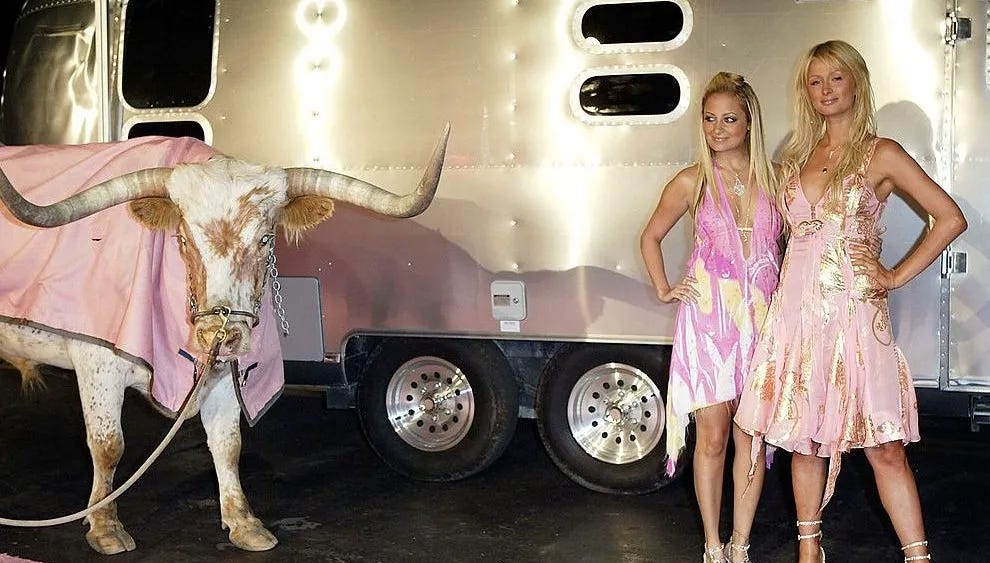

One could laugh at the cosmos of Nicole and Paris in The Simple Life because the absurdity depicted was a world unto itself. Cameras, mics, crew members, and on-screen personality offered viewer’s a chance to participate outside of the frame – to knowingly observe a failed pretension to reality (Paris Hilton is playing a character, right? – one would say; her world ends when the TV set is turned off).

Today one no longer laughs at the 24-hour news cycle, nor does its world end when the plug is pulled. The same worldbuilding, once acknowledged as a parody in reality TV, is no longer performed parodically. The filming apparatus is no longer a microcosm but has violently asserted that the screen has no limits. You are a crew member, your phone a camera and mic. Perhaps, you are also a character?

What would a main character do, and why aren’t you doing it?

This is yet another way that fascination remains tethered to physical apparatuses of media, to devices in and of themselves, and not their messages. The dichotomy of content and critique – the screen and the spectator – has been collapsed in favour of indefinitely running broadcasts starring ourselves. ‘Reality TV’ has been indefinitely cancelled, or it has at least eradicated the second term of the phrase.

We’re just bumpin’ that next line of code that opens up into a world, any world, as long as it is a world. As long as it preserves coherency and meaning through narrative-bounding. What is beyond narrative bounding is unspeakable, cannot be included. In this way, the tangible, mundane space of life as a spectator – as a part of a conscientious public – fades from existence.

Social existence – as a space of negotiation, of going against the grain – no longer exists because we no longer live there. We’ve been relieved of the difficult work of selecting what warrants our attention for ourselves by 360-degree programming which smooths out all contradiction and engulfs the horizon of possibility.

The work, however, which we’ve been relieved of, is the work of politics.

Just as media do not mediate, politics is no longer (perhaps has never been) the domain of governing life. Politics is the perpetuation of stagnation, atrophy, and the decomposition of autonomous responsibility for oneself.

This is brat politics – a colour (#8ACE00), a font (ABC Rom), a meme, a vibe – where circuits of mediation always fail to mediate, and where politics only refers to systems for coercing the undead.

Brat summer is at an end. It always was.

Or, rather, it was always just scheduled programming. Brat summer never began.

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor. 1962. “Commitment” in Aesthetics and Politics. London: Verso. 196-216.

Baudrillard, Jean. [1972] 2019. “Requiem for the Media” in For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign. Trans. Charles Levin. London: Verso. 171-195.

Baudrillard, Jean. [1978] 2007. In the Shadow of the Silent Majorities. Trans. Paul Foss, John Johnston, Paul Patton, & Andrew Berardini. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: Signet.