Bed Chem

Playboy's Haunted Mansion

Throughout the 2000s Playboy was everywhere – on television, in movies, on clothing. The bunny was omnipresent. And along with the bunny, its creator: Hugh Hefner. As depicted on the reality television show, The Girls Next Door (2005-2010), Hefner was surrounded by a small army of blonde girlfriends, playmates, and Mansion staff. Always in pajamas, seemingly at perpetual leisure, Hefner’s daily activities were facilitated for him by a team of handlers.

His food was brought in advance to restaurants, because Hefner never seemed to order from any menu but his own. An hour-long plane ride required a cooler that would be fit for a camping trip, just in case Hefner had one of his standardized snack cravings. And annual parties, movie screenings, and games nights were observed like statutory holidays.

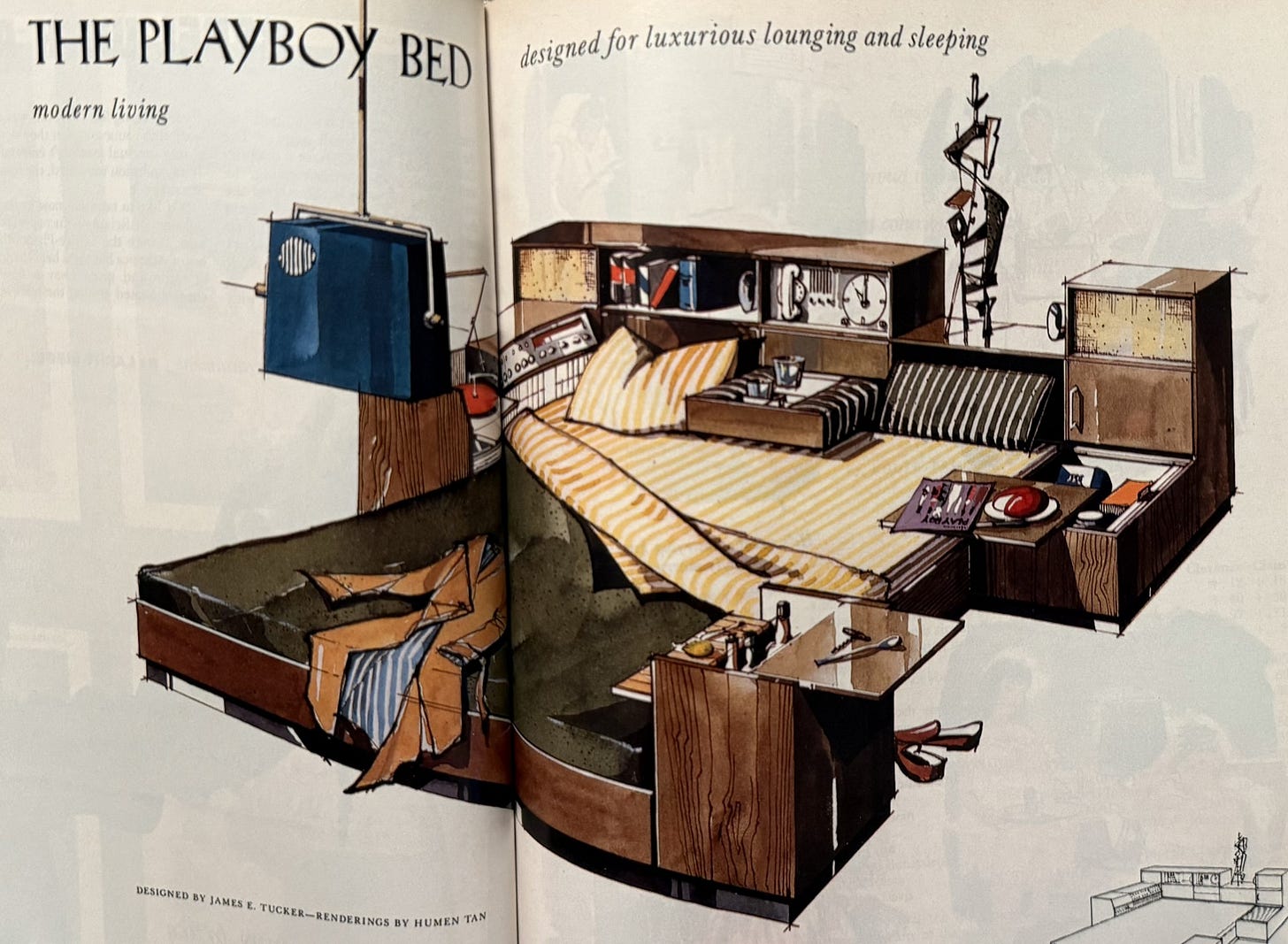

Perhaps most importantly, even Hefner’s bed automated mundane activities. At once an office, living space, and bedroom, the famous Playboy bed was a nexus of activity. It was both private and public; a never-ending sleepover where one could do everything other than sleep. A sleepover where bedtime never came.

Every boy’s dream.

Like childhood, however, the bed is a place for neither leisure nor labour, but something that ambiguously flits between the two. The bed is a place for introspection and sleep, for a respite and retreat that necessarily precedes a capacity for maturity, creativity, and work.

As Jonathan Crary aptly put it in his 2013 book, 24/7, “sleep can stand for the durability of the social.” That is to say, sleep constitutes a dimension of experience, common to all human beings, from which no commodity can be extracted and during which a small scrap of autonomy against exploitation is preserved, regardless of the conditions of one’s waking life. The social endures through sleep precisely because change begins with a dream.

The Playboy bed encapsulates what Crary describes as the late capitalist effort to eradicate the social, to attain a stasis that can be managed – in a corporate sense. Late capitalism inscribes every dimension of life into “a time that no longer passes.” This time is 24/7 time, a time that no longer requires respite from the day. This is precisely because with each drop of behavioural data, cash, and time that is wrung from us, we are, in turn, stimulated by a perpetual fulfillment of needs. Even exchange, one would think. We thus consent unthinkingly to any terms and conditions, so long as we remain conditioned to desire the dopamine of likes and comments, of parasocial connection, of Kardashians telling us to ‘get off our ass and work,’ of decadent Dubai chocolate, and of ever-indispensable Labubus.

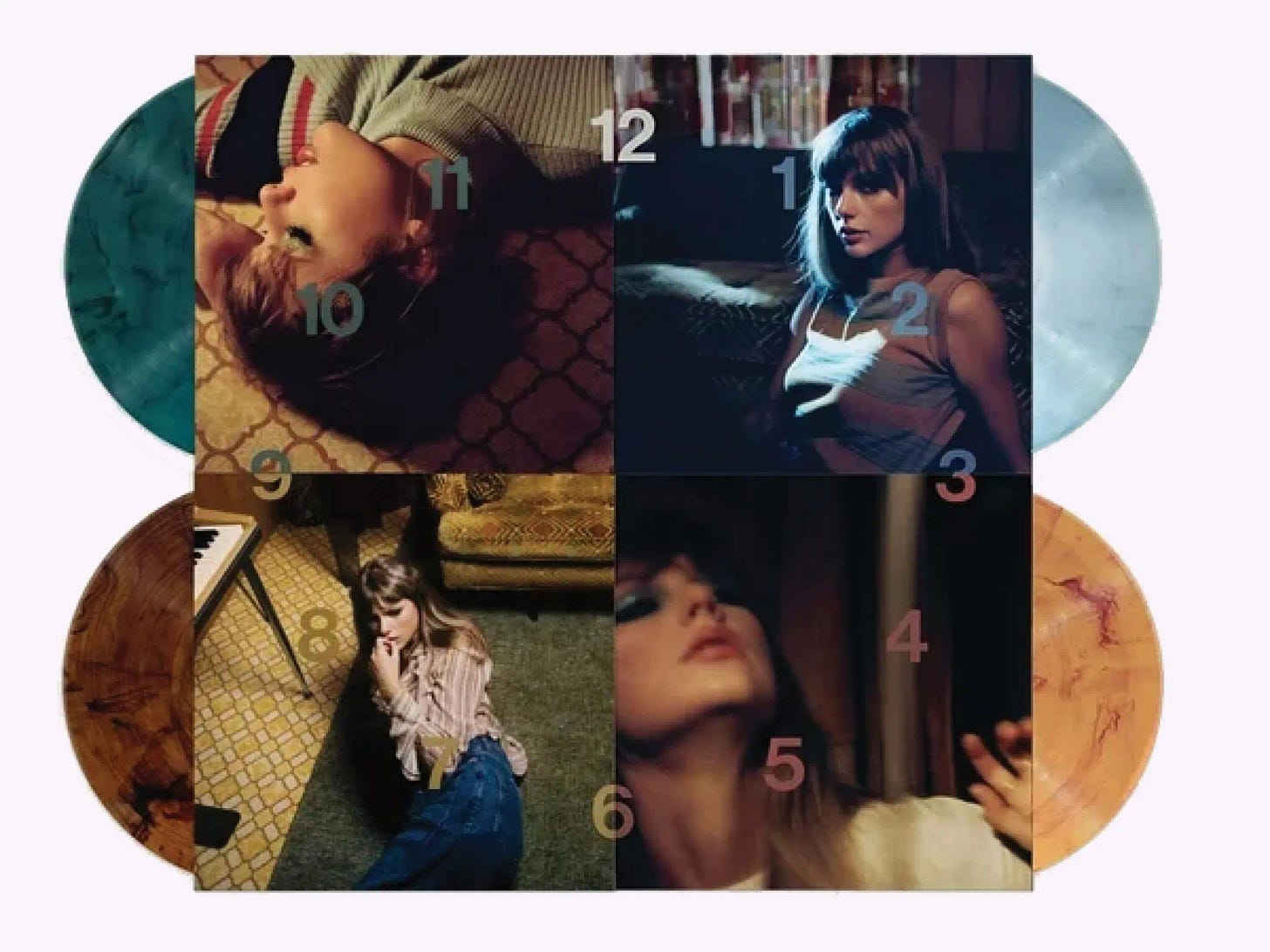

It is no surprise that pop cultural artefacts are produced, today, at previously unthinkable speeds – multiple franchise films in a year, seasons upon seasons of reality shows which have already unfolded in real time on TikTok, annual albums, and monthly vinyl variants. Such patterns of production, both varied yet homogenous due to their sheer volume and speed, appear as a defence against a kind of pop-cultural ‘post nut clarity.’

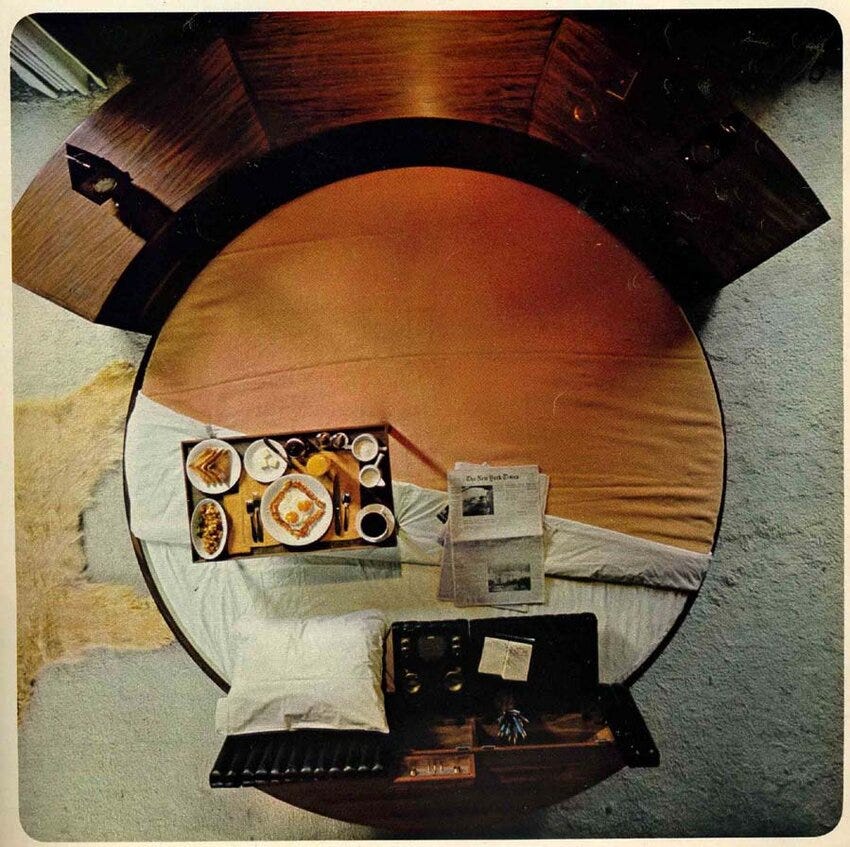

So, too, the Playboy bed is the ultimate defence against respite. In its initial form, introduced in the April 1965 issue as a fixture of Hefner’s Chicago Mansion bedroom, the Playboy bed was a circular, rotating contraption, popularly parodied as a cliché of ‘60s excess in films such as Austin Powers. Yet unlike the parody bed which is clearly meant for excessive sexual performances, Hefner reminisced that the Playboy bed’s purpose was purely architectural. It was not meant to be a stage on which acts of sexual prowess could be exhibited from all angles. It was, instead, a viewing platform from which a solitary, domestic subject – the playboy – could perceive all aspects of his home without exerting any motor movements. These were, instead, delegated to the motor of the bed. In this way, with the click of a button, Hefner reminisced that he could “separately face the television area, the fireplace, the desktop headboard, or the dining area.”

Paul Preciado noted that the bunny subjectivity produced by Playboy was a uniquely domesticated man. Indeed, it is not insignificant that in a column titled “The Playboy Philosophy,” which spanned a whopping twenty-five issues (starting in December 1962), Hefner postulated that his magazine was something of a compromise. An anti-Puritanical sexual aid that enabled bachelors to pleasure themselves in solitude. Certainly, Playboy positioned sex at the forefront of its brand. Yet unlike Penthouse, Hustler, Cheri, and a host of men’s magazines that emerged throughout the 70s and 80s, Playboy only offered voyeurism instead of intercourse. Not only is intercourse absent, but so, too, is a man whose presence is always felt.

Abandoned cufflinks, glasses, a tie draped over a chair – the playmate is alone, but only recently. She is never a wife, never at home, but is instead a ‘girl’ paired with a bunny ‘boy’ who may or may not be the magazine’s reader. Perhaps she is a ‘girlfriend,’ but in either case she is only ever ‘next door.’ Intercourse with her is taboo, since the playboy is inevitably a bachelor. Hence it is really only her image that the playboy is ever in contact with, she can only be peeped at. And even then, the image can only be impressed upon his retina through the assistance of external apparatuses – the camera or binoculars, but never the naked eye.

The January 1989 issue introduced a new model of the Playboy bed, installed in the Hollywood Mansion. This second bed was Hefner’s home base throughout The Girls Next Door. This new model offered Hefner not only a viewing platform but literally collapsed his entire environment into the four-poster confines of a gigantic mattress. The bed frame contained speakers, a bookcase, a telephone and dictating machine, a refrigerator, record player, and an open shelf for “objects d’art.” Like a full mind-body prosthesis (perhaps the closest one could get to Freud’s ideal of ‘prosthetic godhood’), the new Playboy bed could practically absorb the prostrate subject. The subject would be nourished, offered a channel for communication, and amused. Even their inner thoughts could be dictated and preserved inside the bed, a more permanent second body.

The revival of ‘60s kitsch among pop artists, such as Sabrina Carpenter, turns the tables (the bed?) on this solipsistic involution of male sexuality. Instead of domesticated stasis, Carpenter’s aesthetic reconfigures the circular bed as a platform for exhibiting the spectacle of sex (“have you ever tried this one?”). By the 2000s, Hefner had long ejected his own circular bed into the Playmate house: a kind of brand sorority on mansion property, populated solely by playmates. This move only affirmed the role of the bed, as a site on which sexual prowess could be exhibited, as having always excluded the playboy who – himself, next door – could achieve sexual satisfaction in solitude: as a spectator, not a participant.

One can imagine Hefner like a contemporary King Tut, cocooned in a down-stuffed total body prosthesis, delighting in the possibility of his technologically facilitated eternal life. By eradicating the boundary between work and rest, one could perhaps overcome death in sustaining a waking dream, the perpetual indulgence/avoidance of death’s cousin: sleep. The domesticated playboy, blissfully embalmed in his sheets, could remain “alert and unconscious at once,” as Theodor Adorno wrote of the German masses during the rise of the Third Reich.

It was this mode of sleeping while awake that Preciado had in mind when he connected Hefner’s architectural aspirations to Steven Marcus’ notion of ‘pornotopia’ – the ‘setting’ of pornography. Such a sleepless dream daemonically assails the subject, who is in no position to be roused, for they have never fallen asleep. In pornotopia, too, it is “always bedtime,” always dreamtime but never sleeptime. In pornotopia one has achieved sexual maturity, yet is still inundated by visions of ginormous breasts and penises, corresponding more closely to the size of the mother’s breast in relation to an infant. In pornotopia, the earliest, vestigial sexual objects retained by the unconscious appear as contemporary experiences. Pornotopia is a utopia that is, indeed, someplace: “behind our eyes, within our heads,” as Marcus concludes.

Pornotopia is thus a distinctly modern conception, a nineteenth-century invention, a theatre for screening the otherwise unacceptable reality of infant sexuality that is unconsciously retained in the sexual life of adults. Pornotopia screens this infantile reality in two ways: a Foucauldian repression in which one sexual truth is on display in the foreground, even as another is obscured behind it. Playboy, too, for all of its anti-Puritanical posturing, was always the late arrival of a supremely Victorian sexuality. Perhaps one could say Playboy’s conception of sex was even a distinctly Gothic one (but more on that elsewhere).

Indeed, Playboy’s tense relationship with explicit sexuality is a stunted loop, replaying late-Victorian crises of morality and obscenity. On the one hand, Playboy famously refused publicity which lumped it together with pornographic publications. On the other hand, in Hefner’s “Playboy Philosophy,” he asserts that social inhibitions restrict the otherwise eternal truths contained within each rational individual. “Society,” Hefner proclaims, “should exist as man’s servant, not as his master.”

Such a conclusion is exceptionally appropriate for a man who wished to remain a perennial (play)boy. For it is only in infancy that society terrorizes the drives and desires of the individual. In maturity society is, indeed, the servant of men – of all human beings, and especially of men – who have established an increasingly inextricable system of reified domination and mastery.

Society is haunted by the monstrous conditions of capitalism, whose terror resides in the fact that such monstrosity has always originated from human beings themselves. Indeed, the Playboy bed, like the inner layer of a Russian nesting doll, is the miniature replica of a larger haunted mansion (inside a haunted country, inside a haunted world). The Playboy bed is a veritable casket within a vampire’s castle that reduces the life of the subject to his property, and in so doing relegates the subject to the category of animate object; or, rather, to the category of living death.

Theodor Adorno observed a relevant trend in late capitalism. With the increase of belongings, of a previously unthinkable consumerism, there is an equivalent increase in the precarity of those belongings. Opulence is haunted by its imminent destruction through either orchestrated obsolescence (forced upgrades), accelerated decay (enshittification), and the looming threat of destruction (will my belongings be repossessed; will my home be bombed?).

As Adorno wrote in Minima Moralia, “it is part of morality not to be at home in one's home.” The ghosts of injustice imbue all capitalist production, they occupy every object in every home. But if to live comfortably is to be complicit in barbarism, it is not enough to merely disavow one’s possessions. For the suffering which has long been accumulating within the objects of modernity does not disappear if the objects themselves are abandoned. Indeed, it is how we use these objects that is important: as thoughtless comfort, or as a document of progress that at once retains the memory of its barbarism, to paraphrase Walter Benjamin.

All one can do is bear the terror in order to, perhaps, hear what the ghosts have to say. For these ghosts are not capable of exorcism, they are part and parcel of their abode. Contemporary life is by definition a system of human beings who voluntarily treat others and are treated themselves like things – like furniture. “Wrong life cannot be lived rightly,” Adorno concludes.

It is no surprise that Playboy’s model of sexuality as solitary voyeurism returned with a vengeance at the dawn of the internet age. Instead of a conspiracy of bodies that can temporarily withdraw from the social, we increasingly communicate through secondary objects – keyboards, computer terminals, phones. With each such object, we retain the impulse towards a progress free of barbarism – or, rather, an impossible illusion championed by a decaying modernity.

Much might be said of Playboy’s objectification of women. For example, the Hollywood Mansion gates, protecting the mansions many peacocks, monkeys, and other wildlife, alternately featured signs stating: “Brake For Animals,” “Playmates at Play,” and, eventually, with the arrival of the Shannon twins, “Twins at Play.” Yet ultimately, Playboy’s framing of men and women, boys and girls, is unified as it negates the possibility of thinking through capitalism.

Together, but always apart, the playboy and the girl next door defend against the recognition that contemporary life is a simultaneous source of comfort and crisis. The ghosts in its machines remain inexplicable and terrifying, and the memory of barbarism fades from the account of progress. Perhaps it is the playboy who undergoes a transformation worse than that of a woman becoming a peacock: a man becoming a bed.

Bibiliography

Adorno, Theodor. [1951] 2005. Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life. Trans. E.F.N. Jephcott. London: Verso.

Benjamin, Walter. [1955] 2019. “Theses on the Philosophy of History” in Illuminations: Essays & Reflections. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Mariner Books. 196-209.

Crary, Jonathan. 2013. 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. London: Verso.

Hefner, Hugh M. “The Playboy Philosophy.” Playboy. January 1979: 81-92.

Hefner, Hugh M. & Bill Zehme. [2004] 2012. Hef’s Little Black Book. New York: It Books.

Marcus, Steven. [1964] 1966. The Other Victorians: A Study of Sexuality and Pornography in Mid-Nineteenth Century England. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Preciado, Paul. 2014. Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture & Biopolitics. New York: Zone Books.

“The Playboy Bed: Modern Living.” Playboy. April 1965.

“The Playboy Bed: Modern Living.” Playboy. January 1989: 106-107.

Glad Hef's travelling pantry got a mention.